summary:: What is the place of citing neuroscience for professional counselors and therapists? Does it truly represent what we do, or is it just the zeitgeist to say how X changes your brain in Y ways? Prompted by diving deep into a tiny fraction of a great book, Benjamin E. Caldwell's Saving Psychotherapy.

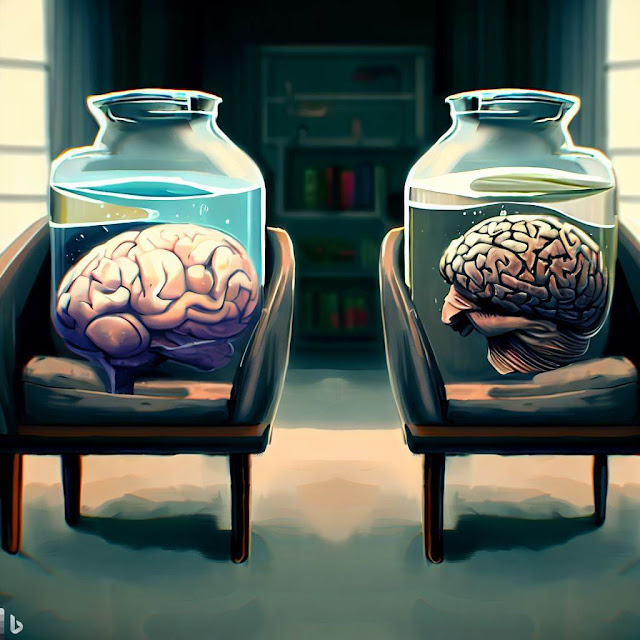

The Talking Cure of Floating Brains

Preface

I love mindfulness; I love counseling; I love critiquing both. At the time of writing (almost a year prior to this post, on 2022-12-30) I was flipping between Benjamin E. Caldwell's Saving Psychotherapy―about professional advocacy for therapists―and Evan Thompson's Why I Am Not a Buddhist―a critique of Buddhist Modernism in its practice and assumptions―all as I was finishing a grueling graduate school program to become a counselor.

Caldwell's book deserves several posts, but I had a library copy and the neuroscience angle (and critique) was capturing me at the time. Strange, but I feel like it must be stated that Caldwell's book is incredibly important reading for any therapist, counselor, social worker, and mental health professional. He is an essential resource when thinking about where and how we can change our profession to meet the mental health needs of our country (and our time).

With that being said, critique is still fun, promotes growth, helps me fully embrace and savor and understand.

The appeal to neuroscience in Caldwell's "Saving Psychotherapy"

I have recently been reading Saving Psychotherapy by Benjamin E. Caldwell. It is an impassioned work from a therapist seeking to reform the many problems in our helping profession. I finished the book over the prior winter, and as I enter the field, I am inspired by many of his arguments and recommendations. A good abbreviation of the book would be: "We can hold ourselves to much higher standards."

However, throughout one section in his discussion of the pitfalls of our field, I think Caldwell falls prey to a line of thinking that also saturates the scientific research into meditation: reduction to neuroscience research as "definitive proof that it works." This post, then, is a bit interdisciplinary, traveling between the worlds of contemplation and conversation.

Change is actually blood flow in the brain

Caldwell organizes his text around "Tasks," which are general reforms that he thinks will greatly improve the mental health professions. One of Caldwell's core Tasks is that therapists need to more openly embrace science. In the process of making this argument, he emphatically states that neuroscience is our most convincing evidence that psychotherapy works:

"Researchers' understanding of neurobiology now offers overwhelming support for psychotherapy, not just explaining that it works but in explaining how and why it works" (128)

"How and why it works"―a bold statement indeed. He goes on to give examples of how neuroscience proves that psychotherapy "works." Such an example includes labeling emotions, which "appears to increase activation in the prefrontal cortex, thereby regulating emotional activation in the amygdala" (128). Rather than the meaning of the label, the understanding of emotion in the context of another human, what is actually responsible for the change of the entire human-in-the-world is, in fact, the change in brain activity. Or, perhaps closer to this argument, the meaning and change is actually just the blood flow[1] and neuronal activity in the individual brain. Truly, this section on neuroscience as the therapist's most powerful proof of change is simply a retelling (regurgitating?) of brain regions that are activated or altered in the process and outcomes of therapy.

We can call this argument reductionistic, in that it reduces the process of psychotherapy to activated brain regions. By extension, it reduces therapy to tampering with neural circuits in such a way that promotes healing. If we just knew what brain regions needed "healing," we could direct therapy that is "proven" to work on "those circuits." By emphatically saying that neuroscience "overwhelmingly" proves how and why psychotherapy works, the entire individual, interpersonal, social, behavioral, and cultural process of healing is reduced to decontextualized brain activity. Yet appealing to neurobiology is not the lynchpin in explaining why therapy works. Rather, it offers one explanation of what ishappening in the brain in the context of therapy.

The many levels of explaining things

The desire to prove therapy's efficacy with an appeal to neuroscience is not unique to our field. This issue similarly plagues the research into meditation and contemplative practices, especially as they impact our wellbeing. Between both fields, the tendency is to collapse or reduce a complex phenomenon into a single, unifying level of explanation. At the moment, the fascinating yet nascent technology of brain imaging is given a preeminent status in our culture, and so serves that unifying explanatory function.

In his chapter entitled, "Reflections on Indian Buddhist Thought and the Scientific Study of Meditation," William Waldron provides a compelling argument that epistemological diversity necessitates several levels of explanation. This will become clear shortly. His example excellently explains this point, which I'll cite in full here:

"Why does the sight of potato chips make me salivate and crave them? One potential answer is evolutionary: in our evolutionary past, long before 7-11s graced our planet, humans evolved to crave scarce but necessary nutrients. We could also answer that at the molecular level, fat and salt play crucial biochemical functions in our metabolism, and our bodies are telling us we need them—now. Physiologically, the neurological networks that connect the eyes, the brain, and the salivary glands recurrently subserve this response. Developmentally, we have learned through personal experience to experience this sight with the taste of salt and fat… Which of these "correctly" explains why we salivate? Or rather, are any of them not correct? Does any one of them exclude the others? Can they all ultimately be reduced to a single correct answer?" (95-96).

Each level represents a different way of knowing and possesses unique explanatory power. You can know the chemical interactions of potato chips in the body and also the evolutionary traits that drive our behaviors. But how does this help you understand a how an individual human develops a craving for potato chips in their life time?

Indeed, each explanation is derived from different methods, models, and constructs, practiced by different researchers in different contexts, and used for different ends. Waldron highlights that the professionals who use their respective levels of analysis cannot readily use the other levels: "The therapist cannot succeed by consulting a chemical analysis, nor the physiologist by listening to childhood memories. They cannot directly use each other's methods, tools, or definitions, since their basic questions, methods, and discourses differ so much from each other" (96).

Of course, this does not preclude therapists from using the understandings of other fields to prove our work. Yet we need to be clear about what questions we're hoping to answer in the process of therapy while recognizing that any one level doesn't give us the full picture of "how and why" something as complex as therapy "works."

Mind (and client) is not brain

The tendency to slip into reducing psychotherapy to neurobiology is understandable. Our culture has a notable brain bias, rooted in western philosophical assumptions of Cartesian dualism and materialism. Despite their crude and static nature, images of the brain are a fairly recent and impressive technological advancement. Our understanding of brain and cognition will certainly continue to explode over the next few decades as technologies advance. Yet these images—and our understanding of what's happening in them—present us with philosophical questions (about what they mean for our understanding of the mind) and pragmatic questions (about whether and how we ought to apply them to our therapy/counseling sessions). Evan Thompson, a philosopher of cognitive science, thinks much about how these questions and our assumptions are intersecting with the scientific and popular understanding of mindfulness. In reviewing some of his work, the connection to psychotherapy will become clear.

The broader scope of Evan Thompson's work has done much to push forward a new understanding of the brain, mind, and environment that is crucial to studying contemplative practices. For example, he utilizes a novel theory of cognition[2] to show how correlating mindfulness practices to brain regions—and using that to "explain" mindfulness—is a conceptual mistake. In Why I Am Not a Buddhist, Thompson makes this argument in a way that can easily apply to Caldwell's claims. Below, I am substituting "mindfulness" for "psychotherapy." Thompson summarizes his argument as follows:

"The first step is that [psychotherapy] consists in the integrated exercise of a host of cognitive, affective, and bodily skills in situated action. The second step is that brain process are necessary enabling conditions of [psychotherapy] but are only partially constitutive of it, and they become constitutive only given the wider context of embodied and embedded cognition and action. The conclusion is that it is a conceptual mistake to superimpose [change from psychotherapy] onto the differential activation of distinct neural networks" (128).

Breakdown: The brain is necessary for the functioning of our mind (and so too for the clients sitting across from us). However, stating that the reason psychotherapy works is because "[c]hanging perspectives builds connections between the dorsal-lateral regions and the orbital-medial areas of the prefrontal cortex" (Caldwell, 128) simply misses a much larger and more practical picture. While I can concede that "neuroeducation" can provide some value as a form of psychoeducation for clients, asking (already curriculum-saddled) therapists to move into the weeds of neurobiology in order to "embrace science" seems impractical.

If the intention is to help mental health clinicians to "embrace science," one must ask about the types of scientific research that can make us more effective. A point which I expand upon in the next section.

As a final nod to Evan Thompson's work, he makes this argument in his 2016 Keynote speech for the Mind & Life conference. If you're interested, the argument begins picking up around 13 minutes with the statement, "We have to stop repeating the meaningless mantra that mindfulness literally changes or rewires your brain. Anything you do changes your brain." (Awkward claps ensue).

Tentative conclusions: One tool among many

By citing these authors, who are both heavily involved in the philosophy of science and Buddhist meditation, I don't mean to suggest that psychotherapy is as tentative as the therapeutic uses of mindfulness. Rather, the nature of the emerging field of contemplative science is examining important cultural (and concomitant philosophical) assumptions that can skew our understanding of individual change. And in Caldwell's brief argument, the assumption is that neuroscience can explain (and so reduce) the entire, multi-leveled process of psychotherapy to brain activity. To assume that this level of explanation is the most "science-based" (and therefore is the most valuable?) is a questionable proposition.

Instead of rejecting the neuroscientific explanation of psychotherapy, I am instead suggesting that it provides one level of explanation. I see two distinct use cases for this level of explanation:

- It can be used as a tool of psychoeducation. Some clients like to know "how therapy works," and neurobiology can be offered as one level of explanation to facilitate client insight and understanding. I am very certain that there are many good educational points at this juncture, but they are essentially psychoeducational in nature.

- It can be used as a tool to "prove" to stakeholders that therapy works. Given my argument, this may sound like I'm contradicting myself. However, it is true that our culture is very obsessed with brain imaging, and we can jump on this hype when necessary to offer another level of "proof" for psychotherapy. I think this is the real motivating factor of this section. For even despite the mountains of evidence regarding the proof for psychotherapy, our culture (especially American) continues to be saddled with stigma around and politicization of mental health treatment.

As professionals, I believe that the most compelling argument for "how and why" psychotherapy works is not a reduction to any specific level, but a holistic argument that captures the many levels covered in our helping relationship. If we had to reduce the "how and why" of psychotherapy to any one level of explanation, the mechanisms for and outcomes of building a quality therapeutic relationship would be more pragmatic for practitioners to understand and communicate. In fact, it would stick with the spirit of Caldwell's argument, as tremendous outcome research demonstrates the efficacy of psychotherapy in creating positive change, something he acknowledges at length throughout the book. Thankfully, we don't have to reduce, and instead we can acknowledge:

- The development and histories of the client in front of us,

- the systems in which they live,

- their access to resources, relationships, and communities,

- their psychological, genetic, and neurobiological factors,

- the quality of the therapeutic relationship, (especially relevant to positive outcomes! and the type of science that makes us more effective as practitioners!)

- the social, economic, political, and cultural context of the therapy session,

- the characteristics and skills of the therapist...

- and the list goes on.

A postscript

I've sincerely enjoyed reading Caldwell's book. I even largely agree that the field of professional psychotherapy needs to more fully embrace science. However, at this point I am skeptical as to why understanding the brain science of psychotherapy would make me a better practitioner (and perhaps this is a blind spot to pursue further!) As a scholar with a background in the Humanities, I view the neuroscience bias as reflective of the larger STEM bias, one which privileges "hard sciences" (like neurobiology) to "soft sciences" (like counseling and psychotherapy research). One is "objective," the other is "subjective"—or so the story goes.

Yet cultural interest in meditation continues to grow, and so is giving rise to distinct, interdisciplinary fields (like contemplative studies and sciences). Perhaps this can also give professional therapists a new home in science, through providing novel understandings that respect the human first-person experience while embracing empiricism and intersubjective agreement.

Footnotes

[1] Blood flow alludes to the fact that these studies often use fMRI, which measures blood flow to different regions of the brain as a subject completes engages in different tasks. The assumption is that increased blood flow equals increased brain region activity.

[2] A theory that he helped create with Francisco Varela and Eleanor Rosch in The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and the Human Experience.